#3 Tokenization of Real Estate

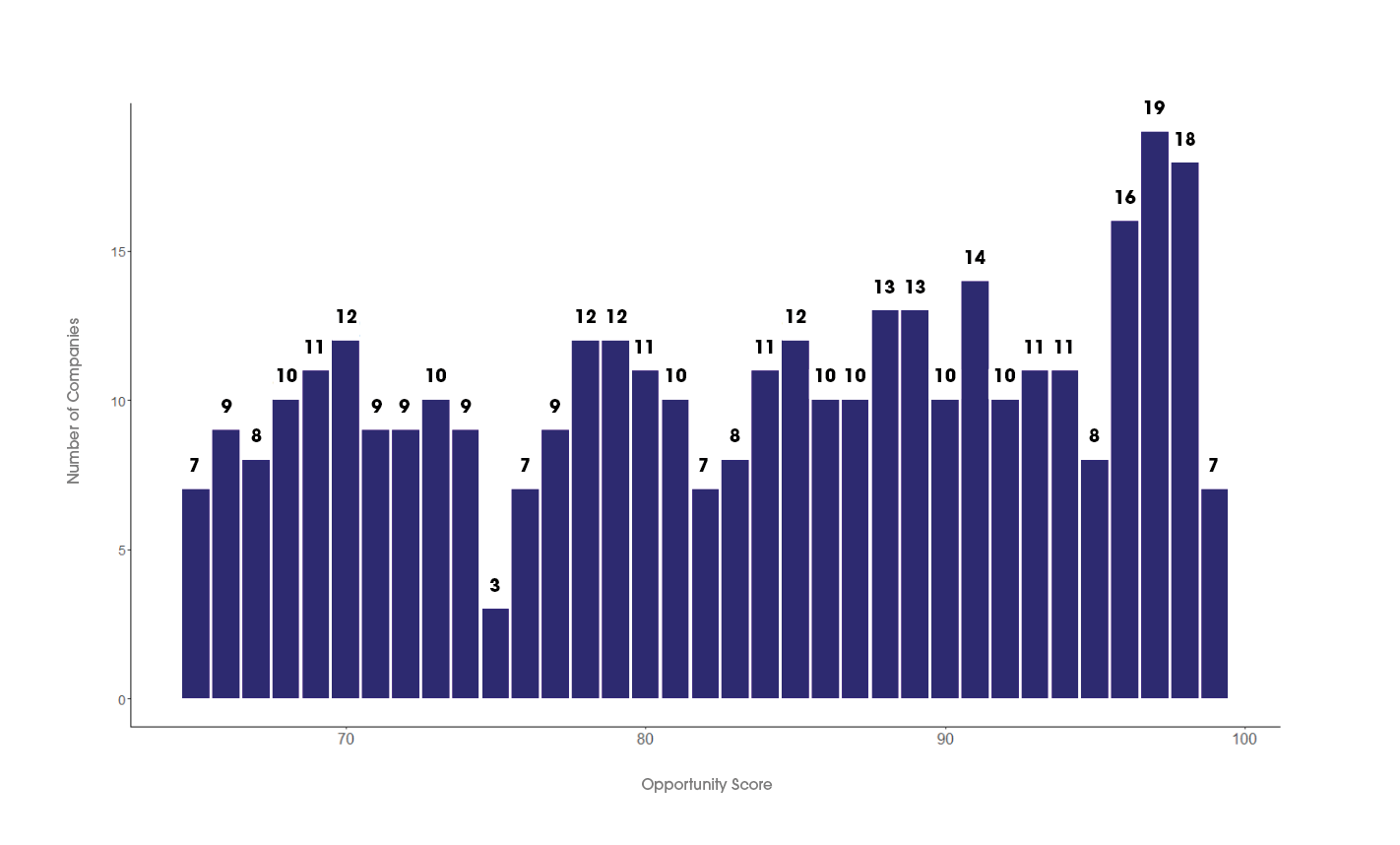

This case study focuses on the tokenization of real estate as an asset class. The tokenization of real estate involves the combination of two relatively distinct asset classes in the market, which are almost opposites. On the one hand, the real estate industry is typically viewed as relatively low tech, but stable in terms of the investment value of properties. On the other hand, blockchain technology is quite advanced, but the tokenization of assets on the blockchain has typically been viewed as relatively volatile, especially after the scares of cryptocurrency markets in recent years. There are more than 75 companies in the PropTech industry that were active deal makers in the past year that are involved with developments in blockchain technology in some fashion. Many of these companies are investment platforms that are using developments specifically in cryptocurrency and payments. Considerably fewer, around 10%, are focused on the actual tokenization of real estate as an asset class. Yet, the promise of tokenization for real estate is real, as it provides a way for investors to diversify their portfolios and create more stable foundations for a flexible stack of assets, while allowing for the necessity of hyper-liquidity and rapid reallocation when necessary, enabling investors to more quickly respond to and capitalize on rapidly changing market conditions.

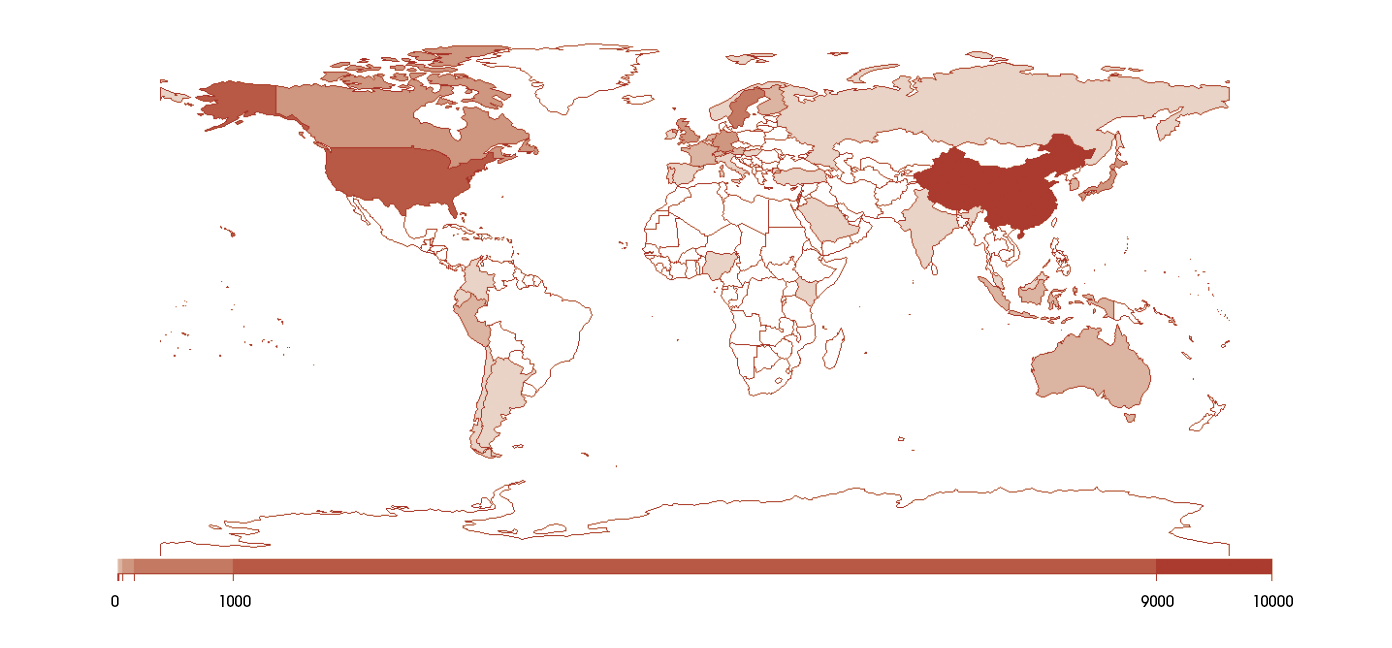

We only have reliable deal data on a total of 54 companies that have PropTech or real estate technology at the core of their focus and include tokenization in the focused descriptions of their companies core activities. Among these, the top fundraisers are Everyrealm ($70.91 million, USA), Finexity ($32.53 million, Germany), RealBlocks ($30.70 million, USA), Parallel Markets ($21.33 million, USA), and Early Works ($15.02 million, Japan). A second tier of fundraisers includes MBD Financials ($10 million, Singapore), Zoth ($6.5 million, India), and Aething ($5 million, USA). Even setting the leaders aside, which are naturally concentrated in the United States, there are precious few companies that have entered the blockchain market in the PropTech ecosystem in core European markets. For instance, there are just two companies in France (Konkrete and Vave) that include the tokenization of real estate in the official description of their core operations. Consider other European markets, there are just six similar companies in Switzerland, five in Germany, just two in Spain (both naturally headquartered in Valencia), just one each in Portugal, the Netherlands, and Italy. Meanwhile, the global leaders for fundraising in this profitable niche of the PropTech ecosystem are the United States ($236 million), German ($32.5 million), Singapore ($17.5 million), Japan ($15 million), the British Virgin Islands ($13.4 million), and Switzerland ($11.1 million). When developing economies like Vietnam and Chile have outpaced key European markets in their fundraising for this cutting-edge technology, we must begin to wonder why European economies have not yet fully embraced this new technology. The answer likely lies in the well-known history of these markets as being rather slow to adapt. Another hypothesis lies in the suggestion that developing markets might be keen to adapt this new technology more quickly, due to the promise it offers them. Blockchain technology, of course, contributes to other elements of the transaction process by improving the liquidity of real estate, through working as though it were a ledger, allowing for increased speed and automation of transactional operations. Advocates also suggest that tokenization could enable new ways of financing home acquisitions for millions of households across the globe, thanks to the endeavors of collateralization and fractionalization of real estate. Together, both collateralization and fractionalization remove enormous barriers for smaller investors, so these elements of blockchain technology are also important to understand.

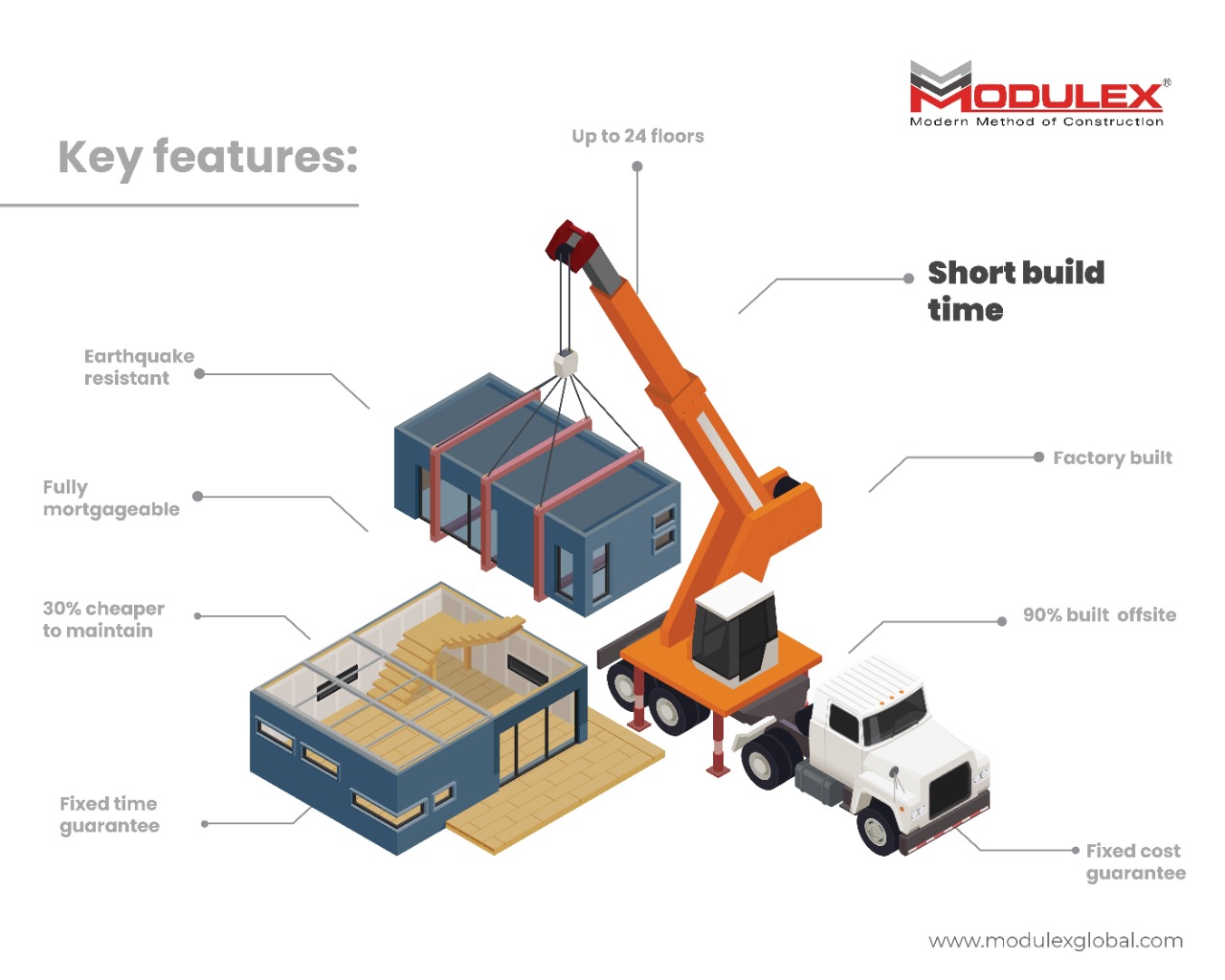

One of the key elements of tokenization of an asset is understanding how the process of creating a “token” works. In real estate tokenization the individual asset, let’s say a building, is broken down into conceivable parts that can be owned, such as apartments. Each apartment can be represented by a digital token, or the entire building can be represented by a digital token. In principle, the token is like a certificate of ownership or a deed to a property. It establishes ownership. However, a token differs from a deed, in that the process can a) increase liquidity, b) streamline processes, c) enable fractional ownership, d) aid in the process of securing funding and raising capital, e) enable easy compliance with regulations, and f) perform legal security checks. Smart contracts can automate the operational processes of the tokenized asset, making transactions much more efficient. In the realm of fractional ownership, tokenization is a key means of enabling fractionalization of an asset. Fractionalization thus also makes it easier to purchase real estate, as indicated above. Further, tokenization of real estate that is presently under development can be a means of securing investor funds, or even used to raise money for initiatives while selling the asset. Finally, in the realm of regulation and security, smart contracts can automatically enforce municipal, state/provincial, and federal purchase and sale regulations, while performing KYC (know your customer) and AML (anti-money laundering) checks to secure transactions.

In terms of thinking about how to tokenize real estate, there are also several different elements of the typical real estate asset class that can be tokenized. To begin with, land tokens can represent total or fractional ownership of the land and property itself. Next, rental tokens can be tied to the income stream from tenants in rental properties. Finally, operation tokens can capture profits from business operations on the property. However, there are typically two paths to tokenization that seem most common: 1) being the equity method and 2) being the debt/loan method. Both use special purpose vehicles (SPVs), which are subsidiaries created by parent companies used to isolate risks and reallocate assets to investors. In SPVs, property investments are typically held within the SPV itself, while companies can transfer property ownership to an SPV and sell off that entity, thus paying capital gains tax, which is typically less than the property sales tax on any given transaction. In the case of the equity method, the asset is simply fractionalized and distributed by the SPV. In the case of the second method, the SPV emits debt instruments that are related to the real estate asset. After careful study, the most rapidly adaptable method in key European markets, such as France, Spain, and Germany, is the latter method. The hurdles to tokenization of real estate are simply lower with the second method, as initial total ownership by an SPV does not need to be established first.

Ultimately the path toward tokenization of real estate in Europe is also subject to contemporary discussions regarding new pending regulations for cryptocurrency and the entirety of the blockchain industry. At the same time, European regulators seem keen to tackle the issue in such a fashion as to not be too aggressive, as there is a taste for allowing for the development of a European flagship company to compete with existing American counterparts. As the European Union will likely adopt a pragmatic approach to the issue of regulation, all eyes are toward a possible solution for RWA tokenization in general, while providing counterbalances to developments in the North Atlantic (with American competitors), as well as in the Pacific and Africa (with Chinese competitors). Thus, there is a motivation to arrive at a solution that will rapidly benefit the European economy as a whole. In the end, real estate tokenization is inevitably part of the future of real estate investment. It allows for a technological overlay that is much needed in a rather typically old fashioned, yet stable, asset class. Tokenization also promises ownership of on-chain fractions of real estate properties with a very low bar to entry, thus entitling the owners of tokens to yields and liquidity in emerging secondary markets. But cutting inefficiencies and transaction costs, tokenization enhances the process of democratizing investment capabilities for all.